Many devices today support sharing video and audio to a separate device. Getting it to function can sometimes be simple and sometimes be difficult, depending upon the specific devices. Sharing from an Apple iPhone (or iPad) to Apple TV should be easy to setup. Sharing from a Samsung smartphone/tablet to a Samsung smart TV should also be easy to setup. But the word “should” doesn’t always mean much.

Many devices today support sharing video and audio to a separate device. Getting it to function can sometimes be simple and sometimes be difficult, depending upon the specific devices. Sharing from an Apple iPhone (or iPad) to Apple TV should be easy to setup. Sharing from a Samsung smartphone/tablet to a Samsung smart TV should also be easy to setup. But the word “should” doesn’t always mean much.

Wired connection using an HDMI cable

Regardless of whether the TV is a “smart TV” or not, you may be able to connect the mobile device to the TV via an HDMI cable, set your TV to use the HDMI input rather than television. However not every smartphone or tablet supports this. For example, Motorola smartphones apparently do not support it.

Current iPhone models have a Lightning port and you will need a Lightning-to-Digital-AV-Adapter. (Rumor suggests that upcoming new iPhone models will instead have a USB-C port.)

An Android phone probably has a USB port. (Specifically, newer models within the past 18 months will have USB-C.) You will need a USB-to-HDMI adapter … or possibly an MHL cable, but most devices do not support MHL.

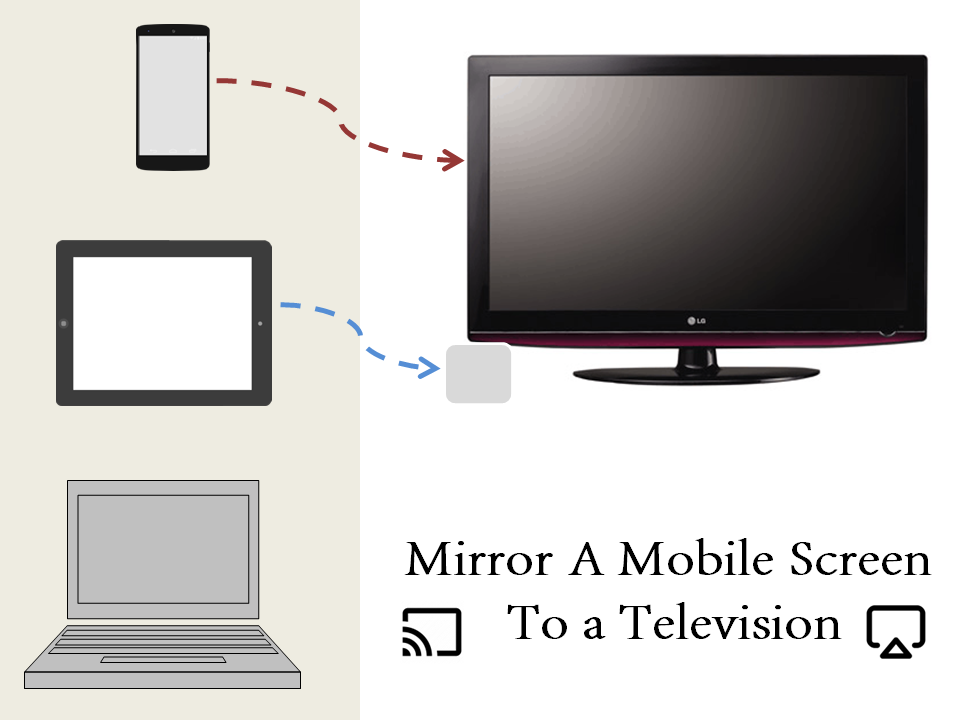

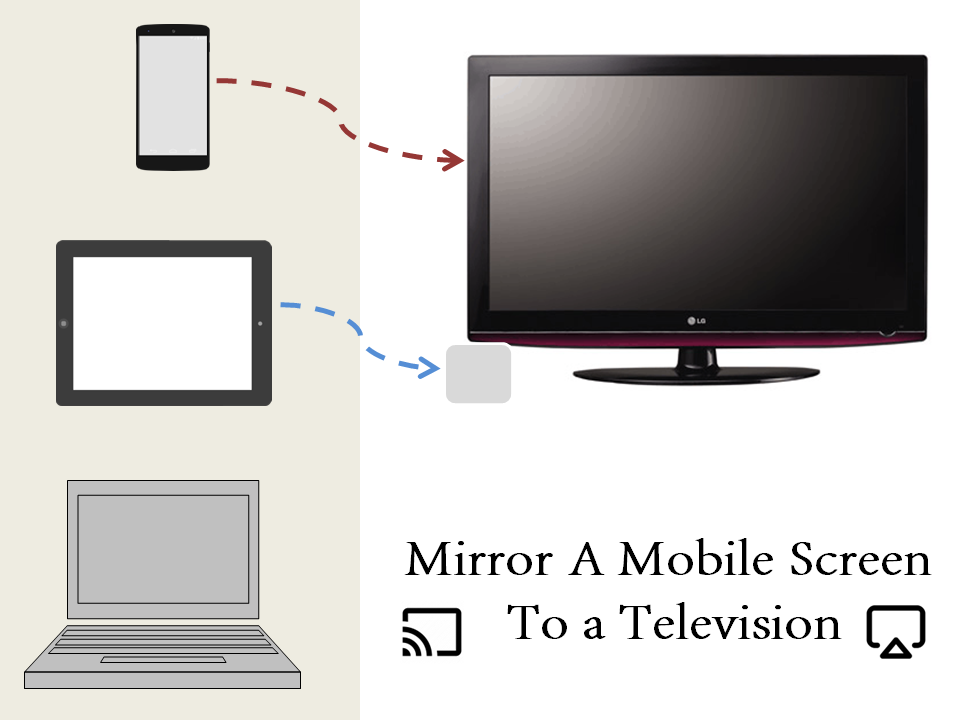

Wirelessly connect a smartphone/tablet/computer to a television

If a TV is not a smart TV but does have HDMI input ports, you can attach an external device to the TV which effectively adds “smart” to your dumb TV. Common external devices that support wireless sharing include:

Google Chromecast, EZCast, Apple TV, Samsung AllShare, Amazon Firestick, and Roku.

Using your smartphone/tablet/computer as the sending device and your smart TV as the receiving device, there are two basic requirements:

- The two devices must be on the same local network (e.g. your home wi-fi).

- The two must utilize the same stream-casting protocol.

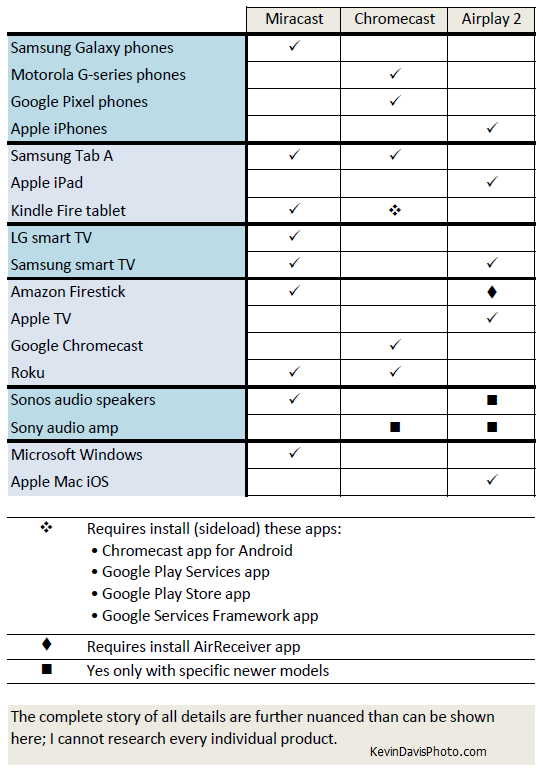

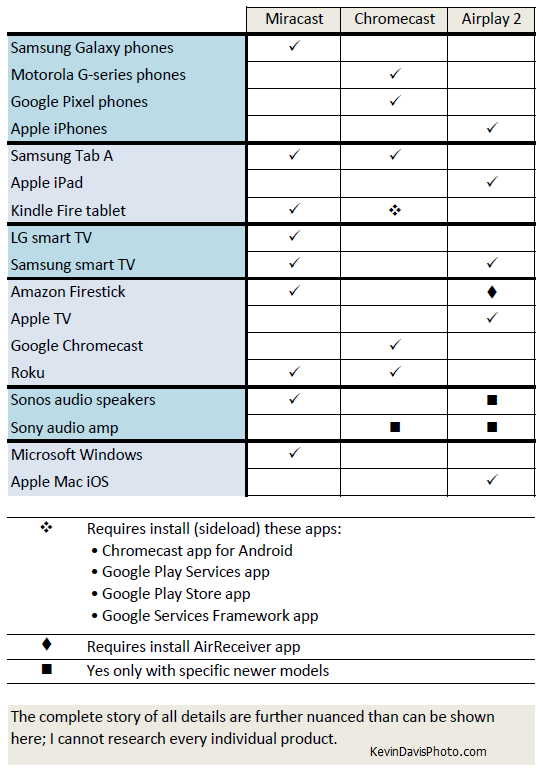

The three dominant protocols today are: Miracast, Airplay 2, and Google Cast (a.k.a. Chromecast built-in) . Samsung’s Smart View is based upon Miracast.

Chromecast will not function without an internet connection; this is not true for Miracast and Airplay 2. Miracast is built upon a standard called “Wi-Fi Direct”, allowing two devices to communicate directly rather than over a network. (AirPlay is proprietary, specific to Apple.)

I have an Android tablet that has successfully connected with two different smart TVs, Amazon Firestick, and an audio amplifier; but my smartphone can only connect to one of those four. The phone supports only Chromecast while three of the other devices support only Miracast. The following table attempts to show such compatibilities and incompatibilities.

Casting

Stream “casting” and “screen mirroring” are two forms of wirelessly sending media (video and/or audio) from one device to another. Although they are different, the term casting may sometimes be loosely misused.

Technically, casting (a.k.a. stream casting) is a feature of a specific application, with support from the mobile device. YouTube, Netflix, Hulu, and iHeartRadio are a few of the apps that support casting. [Note to some friends using the Zoom videoconferencing app: this does Not support casting but you can certainly use screen mirroring; keep reading.]

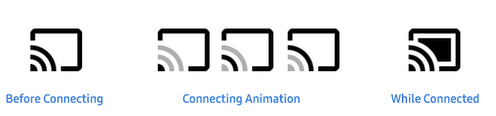

Example: On an Android device supporting Chromecast, go to the settings (swipe down from the top of the screen). Enable: Cast. That should present a list of available destinations (e.g. a TV). The mobile device will send an invitation to the destination and may display the animated icon (illustrated above). Then launching the mobile YouTube app, it shows the connected icon (illustrated above) in the title bar at the top of the app. Upon launching any video within the app, the video and audio are wirelessly cast to the TV.

In the case of a video&audio app such as YouTube, casting to an audio-only device, the video plays on the mobile device as normal while the audio plays from the audio device. I don’t recommend this, as the audio is delayed and no longer synchronized with the video.

Display Mirroring

Display mirroring (a.k.a. screen mirroring) is a feature of your mobile device that wirelessly replicates your local device display on a remote screen (e.g. television). As this mirrors your entire screen, you can use ANY applications and those apps need not include any special features. (Possibly, you may also be able to use your TV as the source and mirror that to another device, but I cannot think of a scenario where that would be useful.)

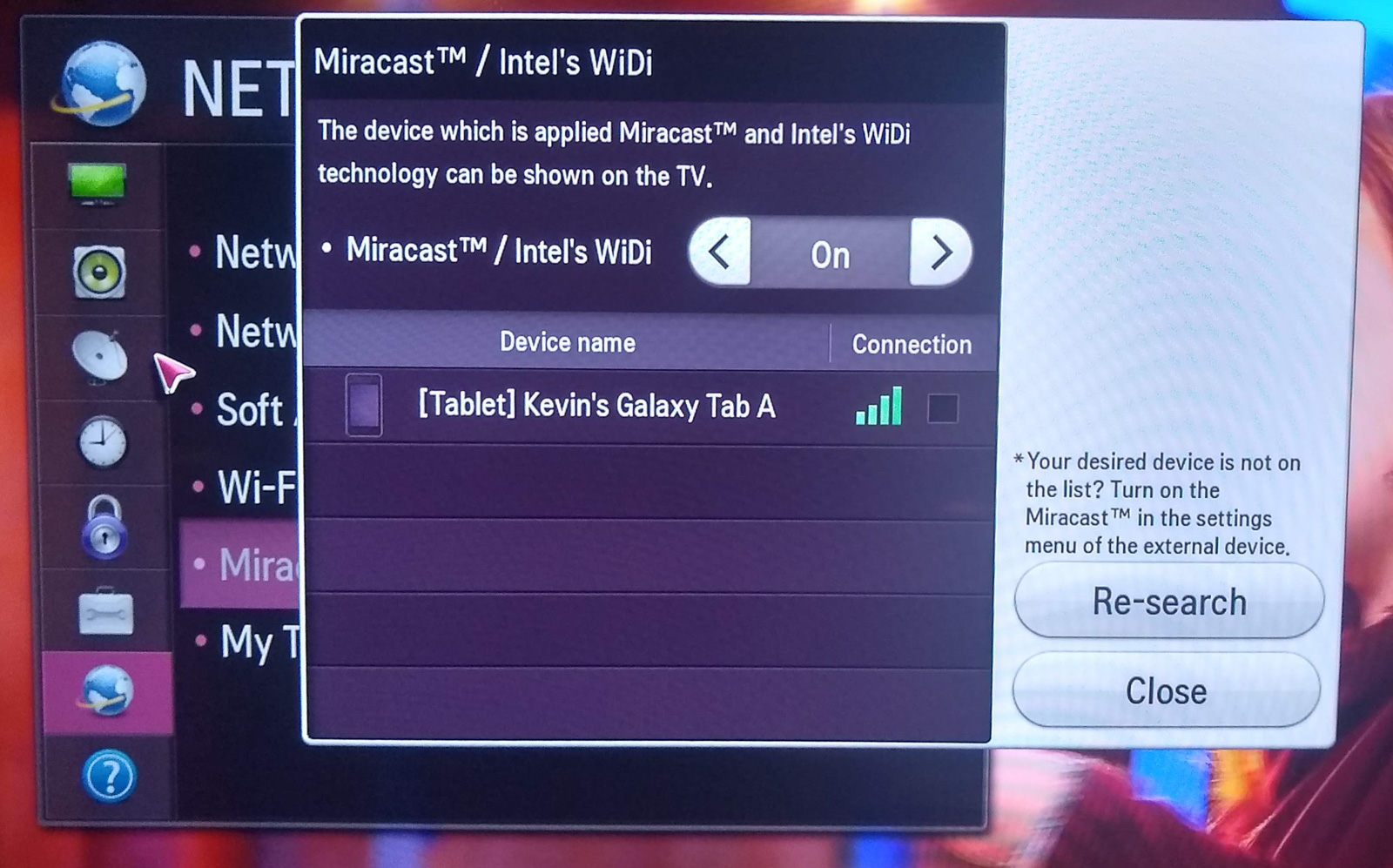

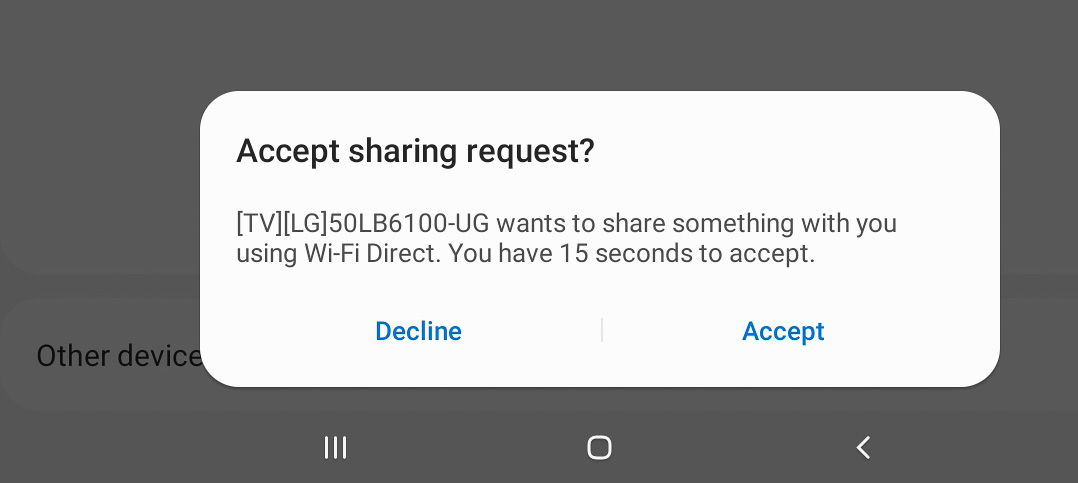

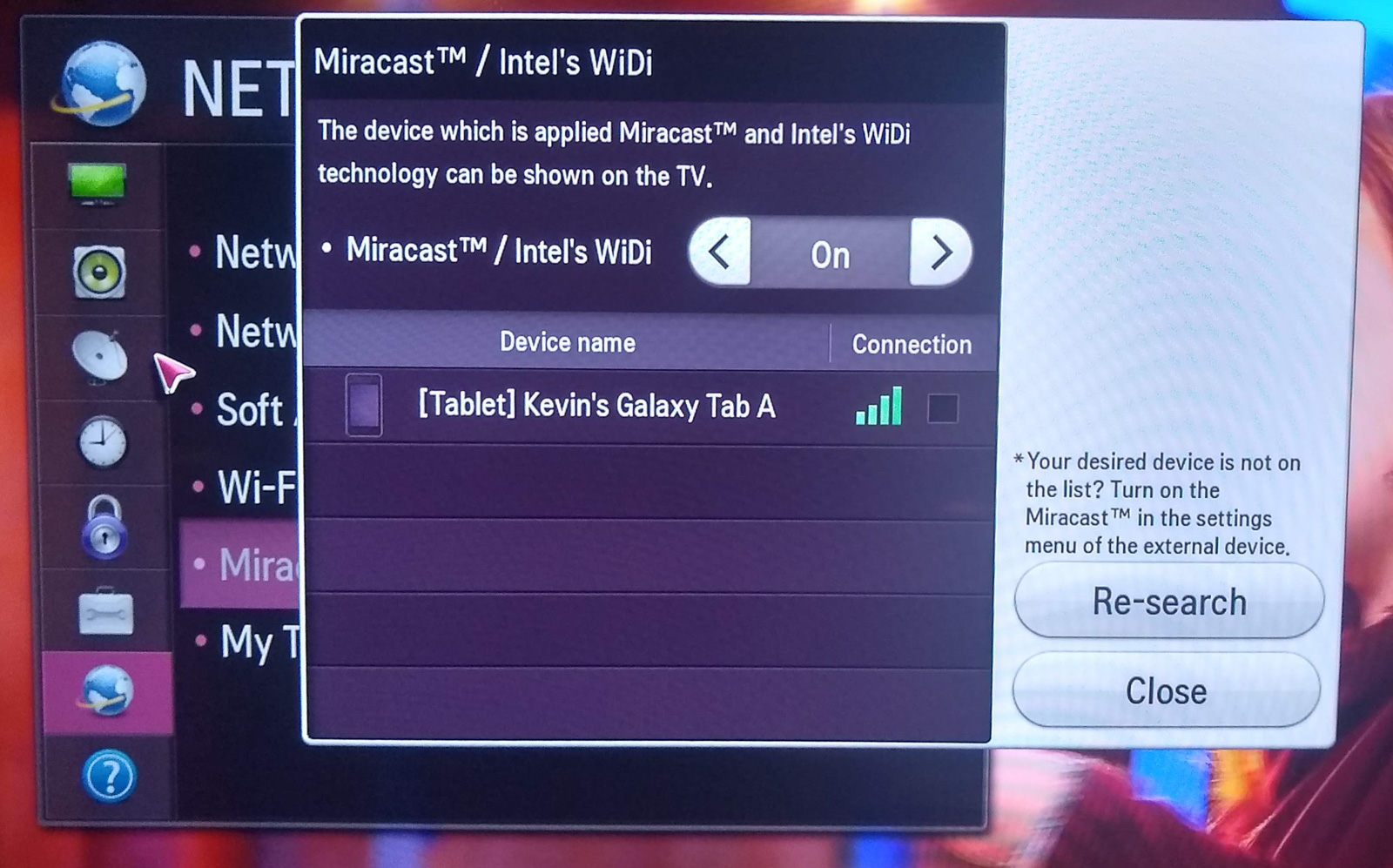

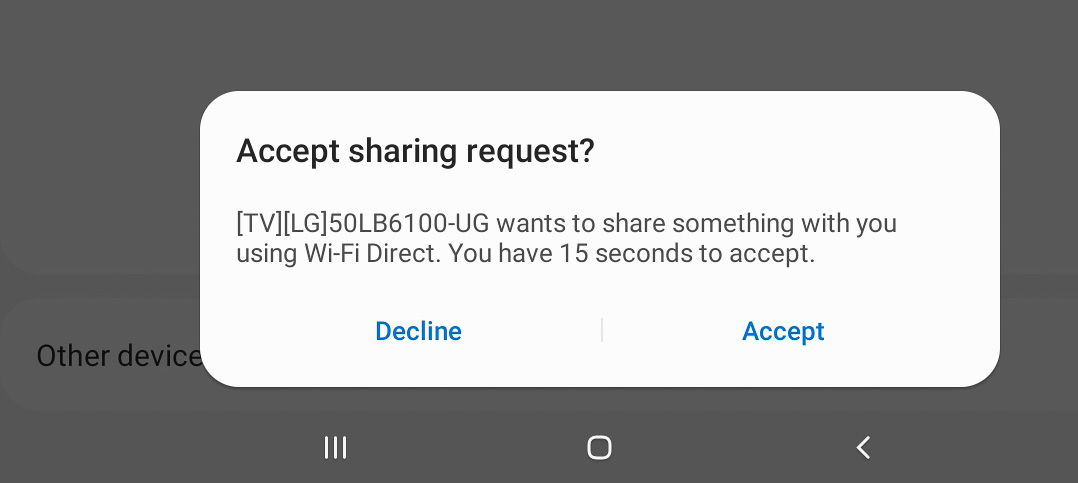

The following photo shows the activation of mirroring on a particular model of LG smart TV. As you can see, the TV has identified that a Galaxy Tablet is nearby and enabled for casting/mirroring. The tablet may then prompt to authorize the connection, shown in the next photo.

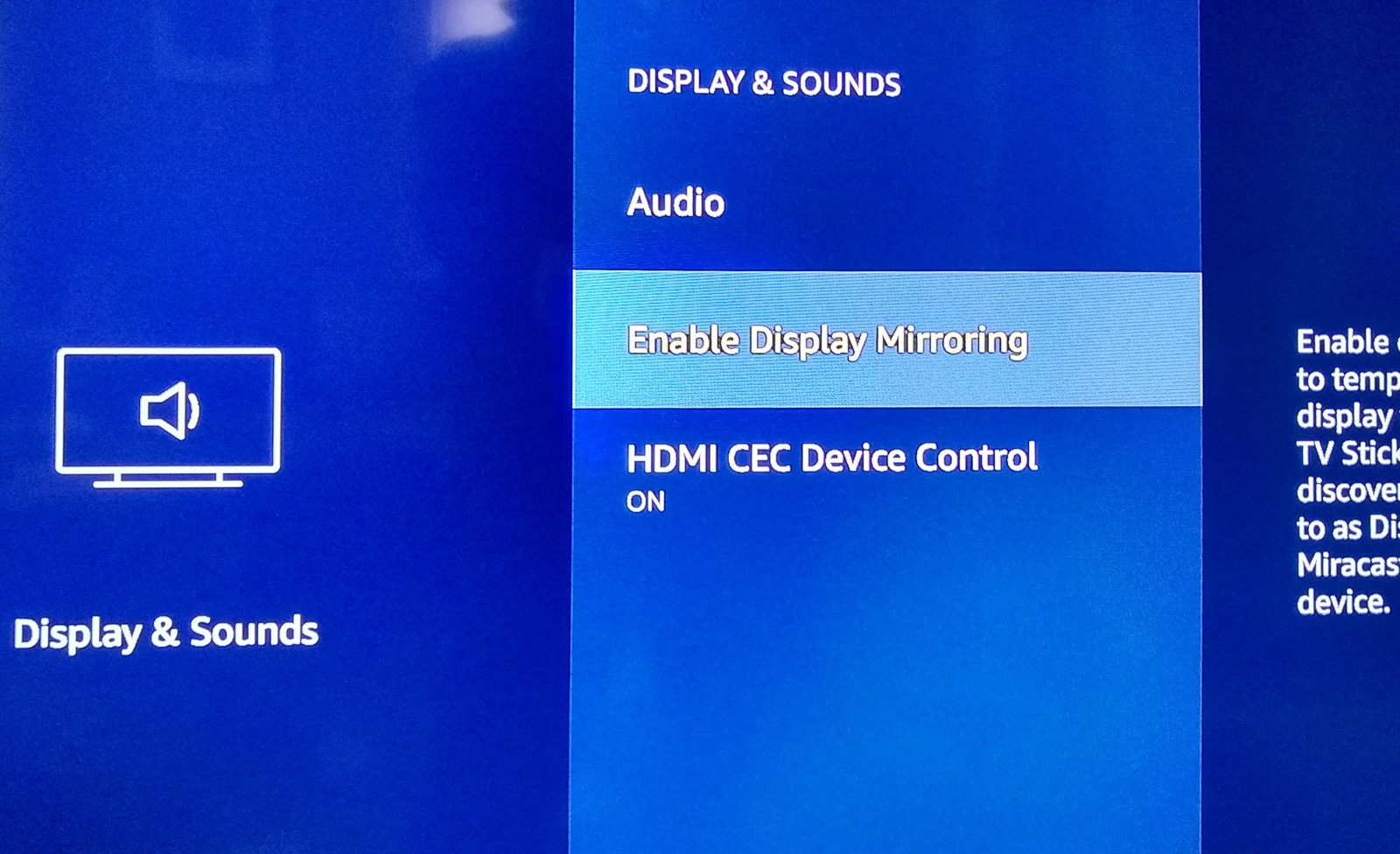

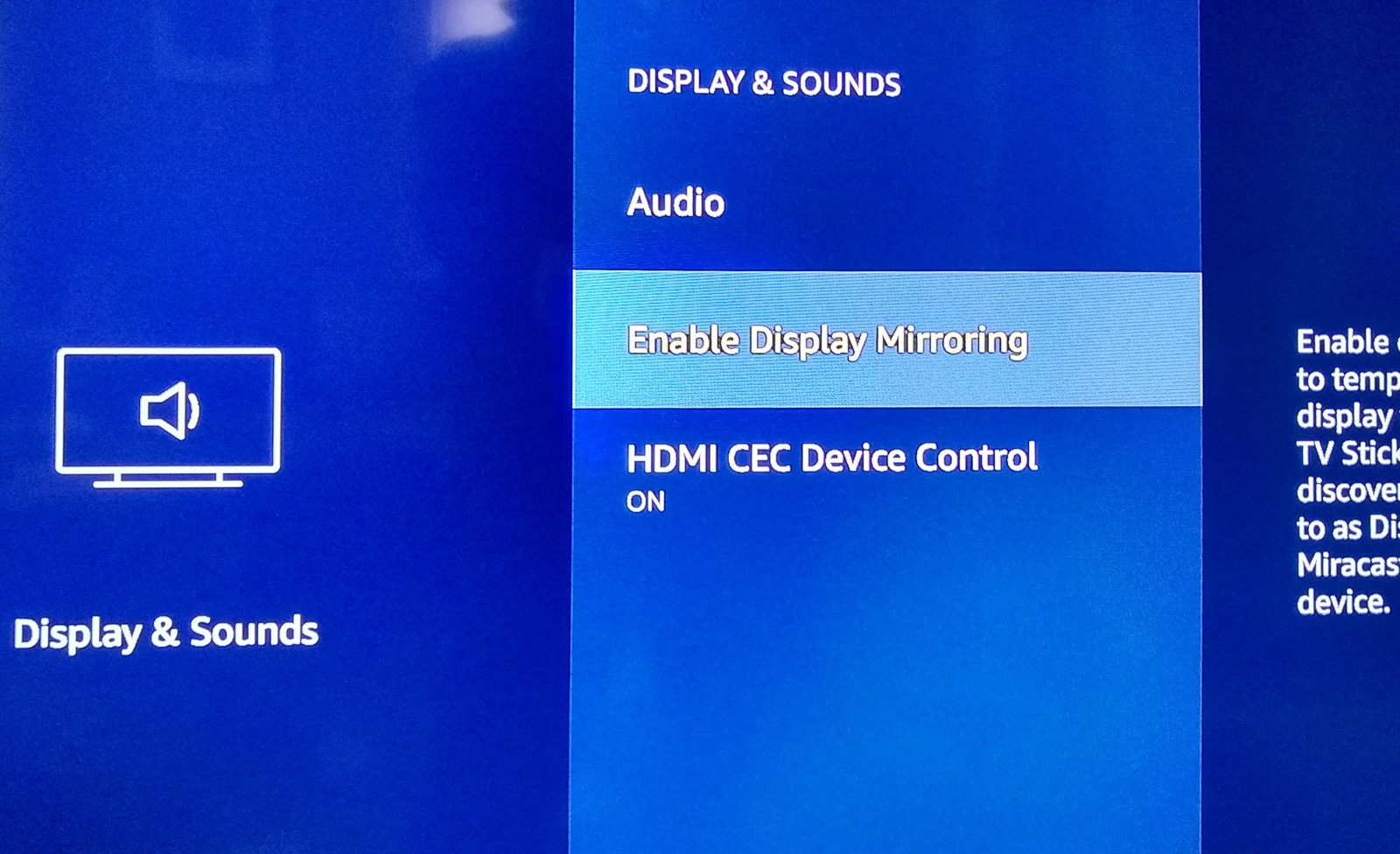

The next photo shows the activation of Screen Mirroring on Amazon Firestick.

Samsung

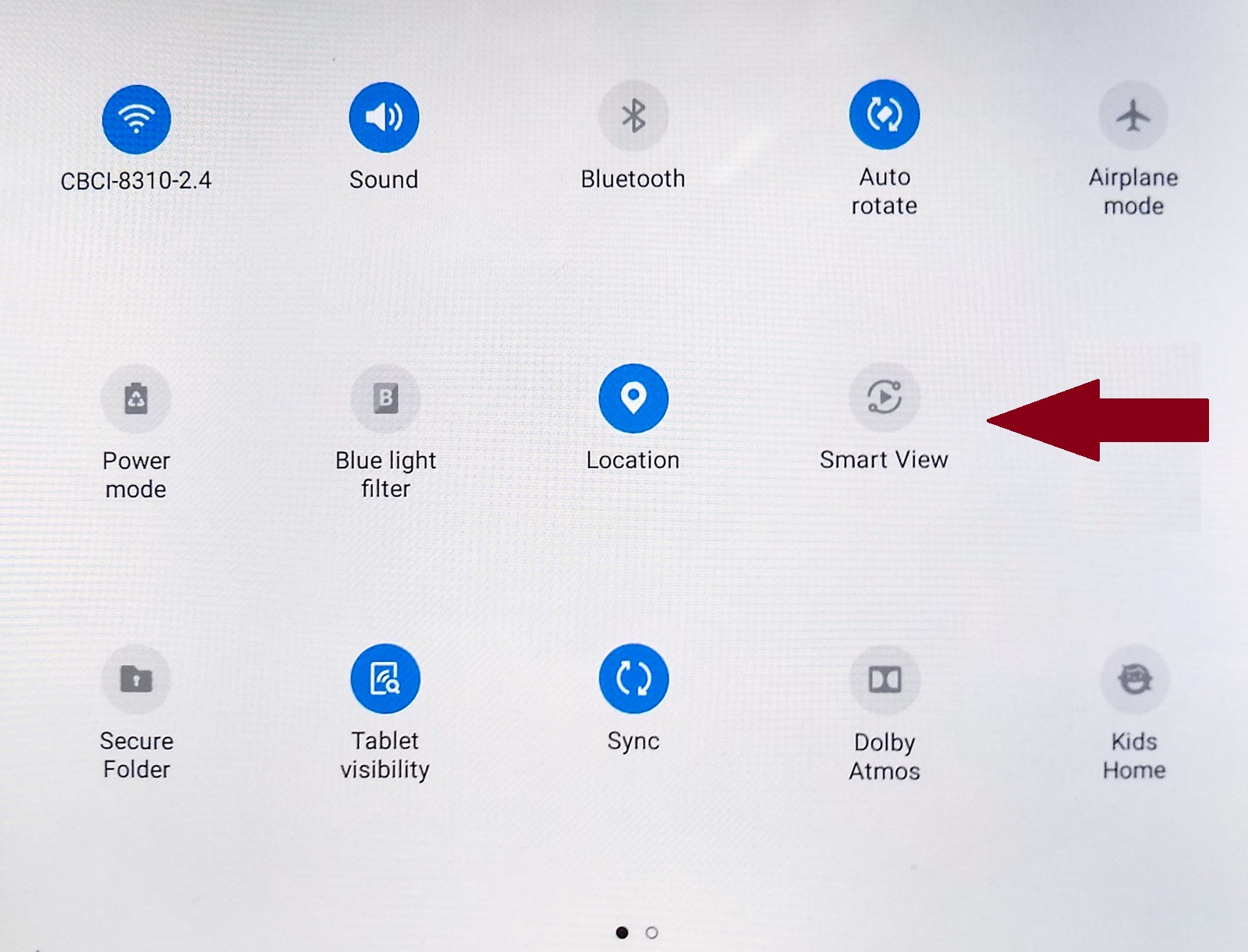

Smart View is Samsung’s brand of Miracast. Smart Things is Samsung’s home automation, with the ability to control many smart home devices, including smart TVs.

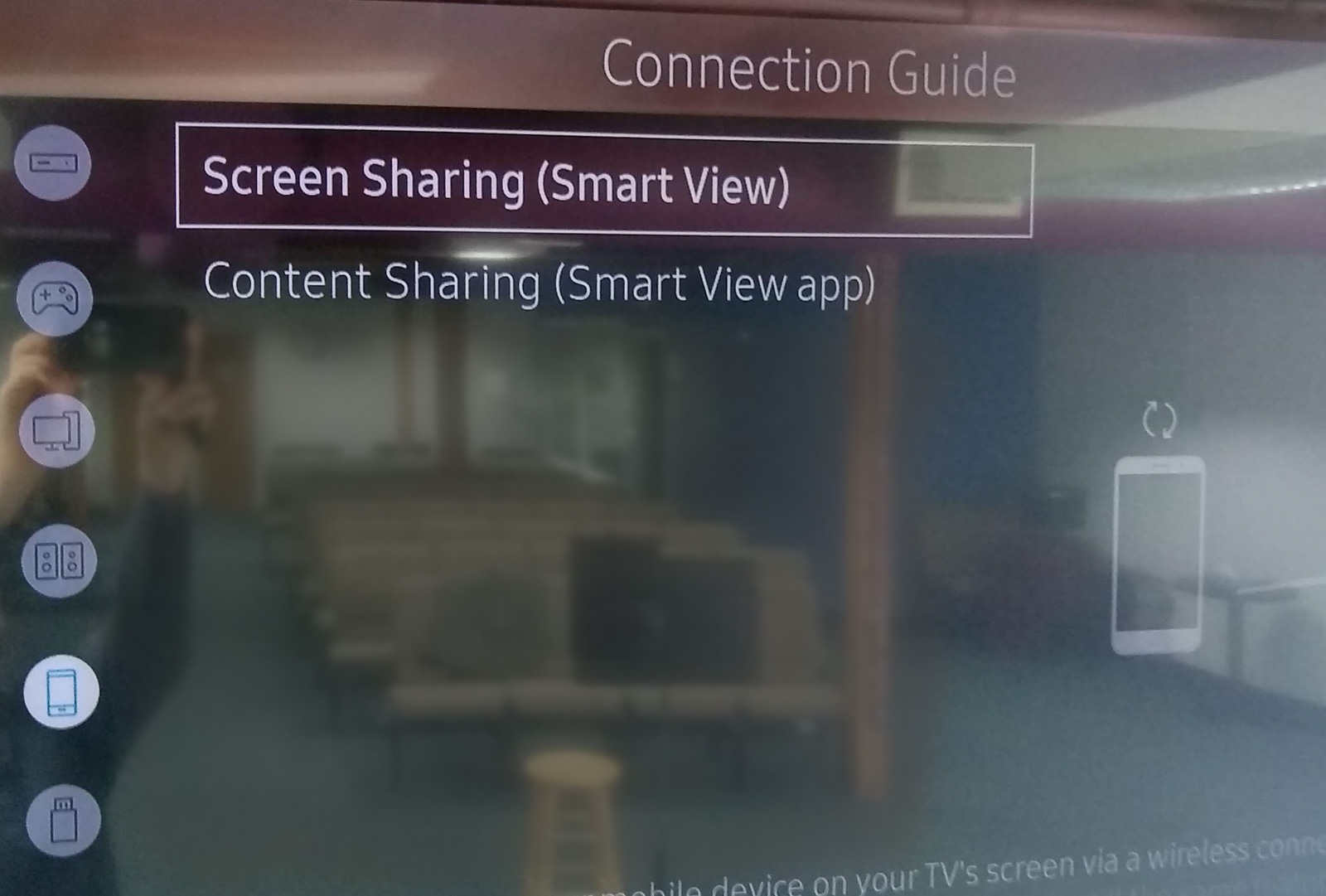

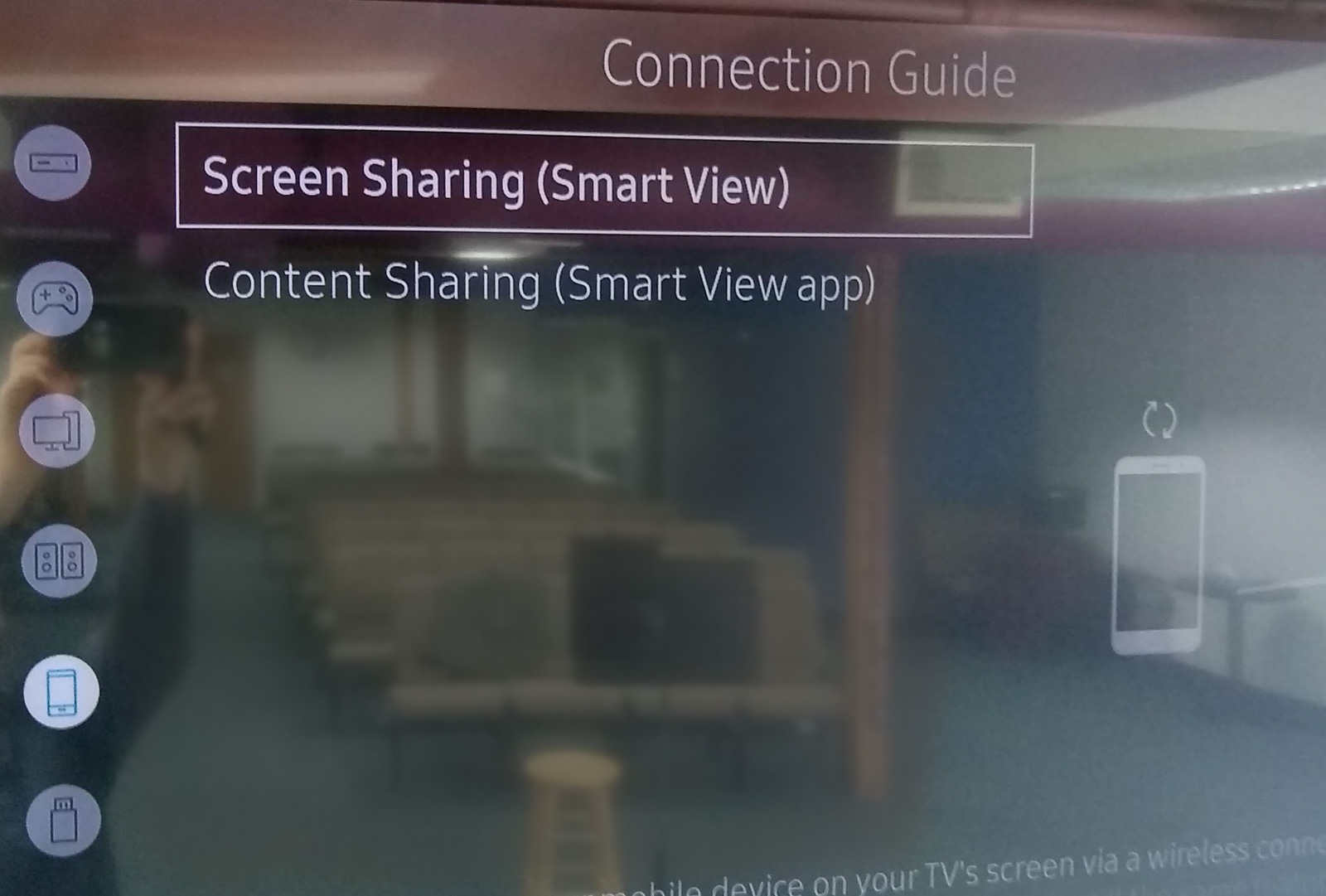

In the TV on-screen menu, go to Connection Guide and enable screen sharing (screen mirroring).

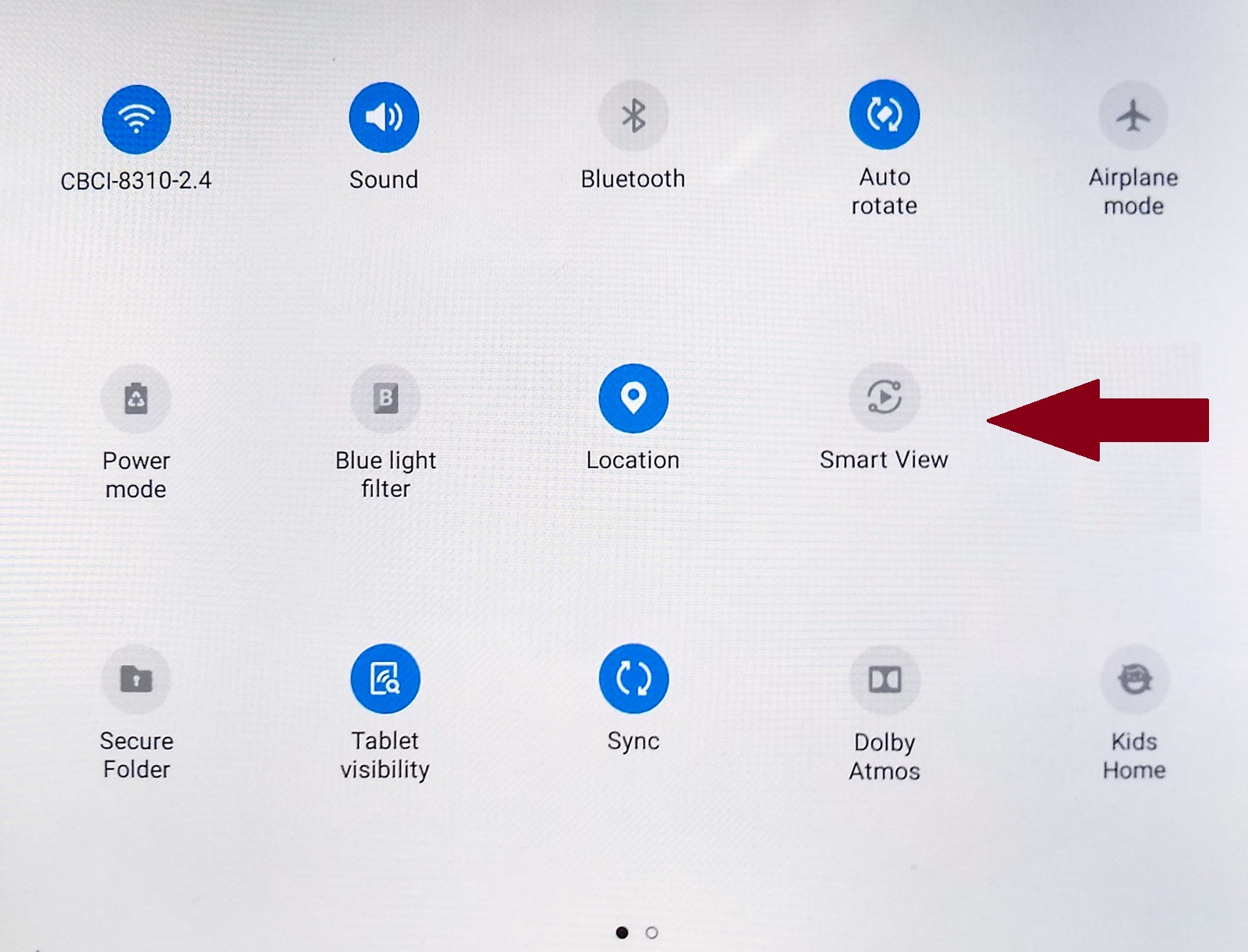

In the tablet settings, enable SmartView, which should then present a list of available destinations, including the nearby smart TV. Easy peasy.

In one particular instance, I easily established mirroring from a Samsung tablet to a Samsung smart TV … but it eventually ceased for an entirely unknown reason and would not reactivate. I rebooted the tablet but that did not resolve the problem. Restarting the TV also did not resolve the problem. Seeing no resolution, I searched online to see if anyone else had encountered this problem and perhaps offered a solution.

In online discussion forums, a couple of separate people reported difficulty with S6 or S8 smartphones wherein the problem was solved by using the Samsung Smart View app instead of the phone’s built-in settings. However, the Android app store included a note suggesting a different app for connecting with newer model TVs – Samsung Smart Things. I installed that and tried it. Although this was also unsuccessful, it did report a useful help message: try unplugging the TV power (and then plug in again). To my surprise, that did resolve the problem.

Other protocols

- Amazon Fling is very similar to Google Cast but never achieved wide acceptance

- DLNA may be available in older products but not used in newer products

- Intel WiDi (Wireless Display) was officially discontinued in 2016

- DIAL (DIscovery And Launch)

April 19 – Boston

April 19 – Boston